Sex, consent and relationships

Te ai, te whakaaetanga ai me ngā hononga tangata

Promoting positive conversations through open discussions around sex, sexuality and consent.

Sex positive conversations

For many a healthy and pleasurable sex life is an important part of having an intimate relationship with others. Whether that's a long-term partner, casual relationship, or mutually agreed brief encounter, it’s vital for us to make sure we’re on the same page. The benchmark for this is clearly expressed, mutual enthusiastic consent. This means being honest and open to conversations with each other around consent and boundaries of others and ourselves. Even when we are in long-term relationships, consent remains a critical part of intimacy.

It’s important that all sexual activities are agreed upon every time, even if you’ve tried and enjoyed them before. All partners in a sexual relationship should feel safe to express their wants, desires, limits and concerns, and have these continued to be respected, no matter the context.

How is consent defined?

-

Consent

-

Consent for kids

Consent is not just the absence of a no, it's ongoing communication about what is desired, expected and off-limits when engaging in relationships. Rape Prevention Education defines consent as a free agreement, meaning that when people agree to do something sexual with each other, they are free from any influence, coercion and intoxication to the point of unawareness.

Consent means people get to change their minds, whether they have engaged sexually with this person before or not. It’s the responsibility of the person who's asking to participate in sexual activity to ensure there is consent, it is not up to a person to prove they are not giving consent.

It’s also important to recognise that lack of resistance to sexual activity is not implied consent. Consent means the voluntary and ongoing process where a person is actively engaging in sexual activity with another.

Important things to know to foster a sex positive space

- Checking in with your intimate partners about their wants, needs, boundaries and limits within sexual activity.

- See consent as an ongoing process. A person consenting to one behaviour, one time, does not mean they consent to that behaviour every time.

- Recognise different ways different people communicate consent, including verbal and non-verbal. Four common cues for sexual intimacy: touching, being relaxed, verbal affirmations and non-verbal behaviours such as being relaxed. Examples include a yes!, kissing back, eye contact, expressing what feels good, actively undressing.

- If ever in doubt seek clear and freely given verbal confirmation. Always check in with your partner that things are still okay. Non-resistance is not consent.

Recognise that everyone has different boundaries and that these can change. Consent can be withdrawn at any time, including during sex. It may be upsetting if this occurs, but it must be respected.

Sexual conduct

Consent matters: Busting the myths of sexual violence

Consent cannot apply in the instances of:

- A person who is intoxicated by alcohol or substances to the point where they cannot consent, or are able to refuse to the activity by way of making well-informed decisions.

- In the presence of any form of threat (implied or explicit), fear, force, coercion, deceit or abuse of power or authority over another person.

- A person is affected by intellectual, mental, physical condition or impairment where they are unable to give informed consent.

- A person cannot consent if they are mistaken about the nature of the event or person’s identity e.g. consenting to protected sex then receiving unprotected sex without their knowledge.

Unlawful sexual connection covers all non-consensual sexual connections in a way which is gender inclusive and covers contact across male to female, female to female, male to male and between people who are gender diverse. Unlawful sexual connection includes penetration of one person to another via, genitals, fingers, objects as well as given or received oral sex without the active participation from the other person.

The spectrum of consent

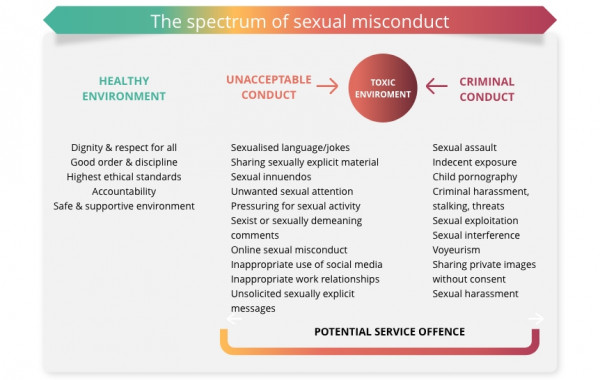

The spectrum of sexual misconduct is a continuum which represents a range of attitudes, values and behaviours. The green area in the diagram describes attitudes, values and behaviours that are considered acceptable and positive interactions. Moving across the diagram are descriptions of unwanted sexualised conduct, which then to flows into the red where we see sexualised behaviours of a clearly criminal nature.

A number of social and contextual factors can make it harder for people to recognise where actions and behaviours fall within this. An action or communication which you may believe falls under the yellow to you, may fall under the orange or red for someone else. We’ve all learned about sex and sexuality from different sources, some of them less reliable than others. One of them being pornography which is aiding in creating unrealistic expectations around intimacy.

Educating ourselves on these behaviours, learning to understand why behaviours fall within yellow, orange and red and the impact that these can have on working relationships is a first step in engaging in respectful intimate and also professional relationships with others.

Non-consensual sexual experiences can also fall along a continuum, as seen in the diagram. Regardless of where a behaviour may sit on the continuum, non-consensual experiences are never okay. The importance of clear communication must be recognised, as without it consent cannot exist. Consent is not a discrete event but an ongoing process of confirmation.

For example, just because a person consents to a kiss doesn’t mean they consent to a removal of their top. It’s important we view consent as communication - without it consent cannot exist. As consent is an ongoing process, it also means that we can withdraw from it at any time. When engaging in sexual activity you should always feel comfortable. If at any point you don’t, it’s your right to stop.

Recognising the problem—the yellow, the orange, the red

Sexual harm and harassment occur in every environment. There is no ‘typical’ survivor and no ‘typical’ person who commits sexual harm. Findings from the New Zealand Crime and Victims Survey (2019) notes over 1 million people (29% of the adult NZ population) have experienced sexual harm or intimate partner violence across their lifetime. People of all genders are impacted by sexual harm, although women were three times more likely than men to have experienced sexual violence. A survivor is significantly more likely to know the person who commits sexual harm; In New Zealand over one third of sexual harm is by a current partner, a quarter by a friend and one in 20 events by a work colleague. None of these events are okay.

Sexual harassment encompasses a broad range of actions and communications. These include unwanted sexual advances; rude sexually degrading comments; discrimination or talking down based on gender, sex, sexual orientation; displaying pictures of a sexual nature without explicit consent; conditions of a sexual nature in return of promotion or training. When harassment occurs it is often spread across multiple areas of the spectrum. This can sometimes be more difficult for someone to address or know how to respond to than a single incident would be. Check out the NZ Human Right’s definition on sexual harassment here and WorkSafe's definition here.

Sexually unacceptable behaviours can become particularly difficult to navigate where power imbalances are in place. Having power over someone can influence the extent to which people feel comfortable addressing unwanted comments, actions or events where sexual contact is unwanted. This usually results from the fear that we may face negative consequences for doing so. In the NZDF we can face power imbalances across a range of avenues including rank hierarchy, age differences, and junior versus senior members of staff and across the types of roles we have. No matter where someone sits, we are all responsible for upholding the same level of respect towards the NZDF community and wider society.

The spectrum of consent described here is not exhaustive. If something happens where you feel like your sexual boundaries have been pushed or ignored all together, it’s not always easy for us to identify or define that behaviour. Sometimes we tend to focus on the ‘red’ behaviours as these are more commonly discussed, because they can be more overt or obvious to recognise. Sometimes when events are not overly aggressive in nature, more subtle forms of sexual harassment or sexual harm become normalised or not acknowledged as sexual violence within people’s relationships and within our community. If an event of this nature has made you feel uncomfortable, distressed or upset, it doesn’t matter if you know where to place it on the spectrum of sexual misconduct—what is important is to reach out for help when you need it. Know that you are not alone in this feeling. You have access to support people for you to talk to about your experiences.

For us to reduce events of sexual harm, it's important to acknowledge the issue. The NZDF is one of a number of organisations in New Zealand committed to addressing this. We intend to create a safe, inclusive and respectful space where everyone in our NZDF community is respected. A part of this is recognising behaviours which are not acceptable and being confident to have open discussions around consent and sex with the goal of preventing sexual harm before it occurs.

Getting help

Sexual harm can happen to anybody, from any background, age, gender, sexual orientation or ethnicity. Whether you are a survivor, or you want to talk to someone about some behaviour you have witnessed or are feeling unsure about, the Sexual Assault prevention and response advisors (SAPRAs) are available at every camp and base.

SAPRAs can provide support, guidance and advice for any form of sexual harm whether that be a sexual offence, sexual harassment, digital communication offences or just that someone has made you feel unsafe or uncomfortable.

To find out more information on our SAPRAs and how to contact your local one click here.

Additional resources

- Safe to talk 0800 044 334. 24/7, private and confidential info and support online, toll free, text or email for anyone affected by sexual harassment, sexual abuse or sexual assault including families of the person accused.

- Kahukura- New Zealand website with info and resources for rainbow communities re partner and sexual violence.

- Living Well- Australian website with resources, including an app, for men who have been sexually abused and their friends, and family.

- Netsafe - A New Zealand website with Info for young people, parents, professionals about all aspects of internet safety, including scams, sexting and much more.

- www.sexualviolence.victimsinfo.govt.nz – If you have been a victim of sexual abuse and you choose to disclose, learn more about the Police and court processes through Ministry of Justice

- Raising Children

- TOAH-NNEST– Additional reading

- Rape Prevention Education

- Shakti International