Healthy relationships

Hononga tangata hauora

Support for our people in building and maintaining healthy connections with others

Healthy relationships and masculinity

Being Men is a New Zealand Rugby (NZR) video series that explores wellbeing, healthy relationships and masculinity from the perspective of New Zealand men.

What is a relationship?

As people we are wired to connect with other people. Historically this has been for survival (food, shelter, clothing, for mutual protection) and to carry on growing the human race. We are not made to live in isolation without connecting to others.

Over time the nature of our relationships have changed due to our society developing and moving beyond the sole purpose of survival. We now connect with people in many different environments. We mingle with others at home, at play, when practicing our cultural customs and at work.

In all these different environments we create different connections with different groups or individuals. These relationships have different meaning to us depending on the reason for the connection and the value we place on them.

- They give us a sense of belonging and identity

- They provide us support and nurture

- They provide us meaning and purpose

- They give us responsibilities

- They give us pleasure and love

- They provide biological or kinship ties

- We preserve and share beliefs or spiritual values in our connections and culture

Relationships are created through formal and informal processes either at an individual level or a group level in the following ways:

- Communications

- Giving and receiving care and support (reciprocity)

- Raising children

- Emotional support

- Culture and family

- Doing work or meeting obligations

- Traditions

- Social roles and structures

- Personal experiences

- Shared activities

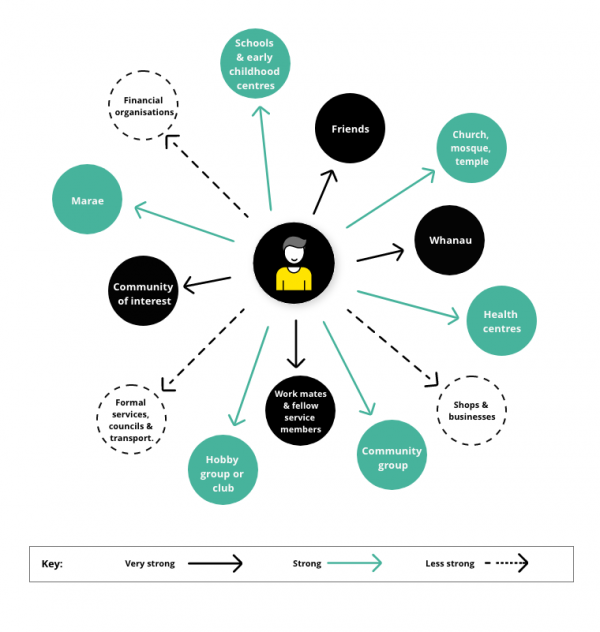

The strength of these relationships is based on their purpose and the meaning we give them. They may also depend on the amount of time we invest in them or spend with others.

Some examples of the difference in the strength of our relationships are shown in the following diagram.

What does it mean to have a respectful relationship?

This includes relationships with any other person, not just relationships we have with partners. Healthy relationships have some key characteristics. They include:

- Behaviours that show care and respect for others

- The ability to have empathy for others—to be able to imagine what it is like for others.

- Communications that enable everyone to have their opinions or views heard.

- Being able to accept others who have a different point of view.

- Negotiating conflict in a safe way and being resilient.

- Showing appreciation.

- The ability to put others’ needs before our own, showing selflessness or empathy, and putting the group needs before individual needs when required.

- Having a commitment for the long term to a partner, significant other and family/whānau.

- The ability to grow, nurture and share affection with children.

Respectful relationships for couples

A shared connection that brings mutual support, respect of values, love and emotionally safe connection, safe and consensual sex, dependability, trust, celebration, fun, sadness or disappointment (when you care for someone deeply at some point there will be a down which impacts you), worry, absence, duty, taking part in personal or cultural rituals e.g., around births, deaths, faith.

Click here for our set of practical tools for you to use and keep in your wellbeing kete that support a healthy relationship.

Consent and safe bodies

To have a healthy relationship with a loved one will usually include having a healthy sex life. A healthy sex life is important to a healthy relationship with a partner and is an extension of being emotionally and physically close with someone. It is an expression that you care deeply about but it can also mean that you have your physical needs met. It is vital for a healthy sex life to talk about consent. This means at all times before having sex with someone you care about you need to make sure you both consent. Consent is about having respect for someone’s beliefs, culture, gender and sexual identity, choices, opinions, personal space, and body. Below are some key tips for keeping yourselves safe.

Do:

- Discuss what you both want from a sexual relationship: what each of you expect and what is okay. For example: how often, safe place, behaviours that are okay and not okay.

- Talk about when it’s okay and not okay to have sex.

- Check in with them if there is anything they don’t want to do or feel unsafe with.

- Check in with them every time before you have sex that they agree (or consent).

- Stop if they say no or are unhappy to continue or seem reluctant to continue.

- Be mindful of times when partners may not want to have sex – if they are unwell, if they have not connected with you for some time, if they are stressed out with work, children, or family commitments.

Dont:

- Don’t put pressure on someone to have sex if they don’t want to.

- Don’t judge or get angry with someone for not wanting to have sex.

- Don’t use social media to talk about having sex or say things about others.

What does a disrespectful relationship look like?

There are some of the things that happen in an unhealthy relationship. They can be divided into behaviours and attitudes:

Behaviours

- There is only one person who makes important decisions for the couple.

- There is no shared management of finances or one person buys (hides) things without communicating the impact on household expenses.

- There is an expectation that things are done one way from one person’s perspective or direction.

- There is no acceptance of each other’s friends or family/whānau.

- There is infidelity (lacking commitment, loyalty or protection of the relationship).

- There is no sharing of child raising responsibilities.

- There is no sharing of household chores/tasks.

- There is overuse of alcohol or other substances.

- One person has become withdrawn or socially isolated from the other and the relationship.

- One person may use violence or coercion/manipulation towards the other—this could be physical, psychological, emotional or neglecting them if they don’t do what is wanted.

- There may be withholding of affection (love, sex, care).

- There may be no self-regulation of thoughts and feelings by one or both people.

- There is no shared quality time with each other.

- There may be avoidance of the other person (spending lot of time—more than would be usual—at work, away, doing own hobbies).

Attitude

- There is judgement or putting down of one person to the other.

- There are threats from one person to the other (I’m leaving, I’m going away, If you…..then I….).

- There is criticism and defensiveness.

- There is ridicule (making fun of or teasing) or belittling of one to the other.

- One person may not feel safe to express their opinion or views.

- One person may be constantly trying to change or control the other to what they think the other person should be.

- There is no comfort provided when the other is distressed.

- There is no empathy (the ability to imagine what it might be like for the other person).

- Controlling or manipulating one person is the aim of the other person.

The difference between healthy and unhealthy love

When is it a problem for us or the team?

When personnel have healthy relationships this supports the wider NZDF team to get the job done. It provides a layer of protection so that when things get tough or hard you have a home team cheering you on to get through. Healthy relationships give us purpose with our role: we want to do well and win on operations both for the work team and the home team.

If we have an unhealthy personal relationship some of the impacts at work are

- May impact our mental health (worry, anxiety, stress, numbing, avoidance).

- Means we may not be focused on the tasks we have, which may put colleagues at risk.

- May create conflict in work relationships as it ‘spills over’ into the work environment.

- May impact on our physical health (sleep, fatigue, chronic health conditions). We may become unwell, we may need to take sick leave which in turn impacts on the mission.

- May impact on our finances.

- May need time out to go to counselling.

- May result in separation and if children involved negotiating custody or shared care arrangements.

- May start seeking comfort in other ways (using alcohol, over work, gambling, retail spending).

- May impact on safety of children or partner/significant other.

- May result in disciplinary charges.

- May result in request for posting/discharge/change in role.

Factors that affect how we form relationships

The causes or contributors for a relationship to change from healthy to unhealthy or be unhealthy from the start are many.

At the society level

- Expectations on roles and responsibilities (gender, family, culture, religion).

- Attitudes about the priority of personal rights and freedoms (e.g. what happens at home behind closed doors is only the business of those involved not the state or formal institutions) versus the importance of individual safety.

- Society expectations for what is acceptable when raising children, such as regarding discipline, that children are required to go to school.

- Society support for those in a relationship.

At the group or organisation level

- How one becomes a member of a group—whether you are an insider or outsider.

- What the rules are for this membership and what is the personal cost to belong.

- What your organisation demands or responsibilities are for your role (hours, identity, shift work, career progression, rewards, remuneration, away time, change in location, housing, community support, access to shared resources).

- What flexibility is there to support those in a relationship being able to change hours or duties.

- What importance is placed on members being cared for if unwell or managing a return to work.

At the individual or personal level

- What is your experience of personal relationships when growing up?

- What did your role models do or say?

- What do your wider family/whānau show you about positive or unhealthy relationships?

- What support is there for you as a couple? What resources can you tap into if things get wobbly?

- What skills (communication) or attributes (empathy) do you have to manage being in a relationship?

- What quality time do you have to spend with your partner (long distance?)

- What are the things which make you feel safe and cared for?

- What is your experience of managing conflict in a relationship?

- What are the expectations you have for a healthy relationship?

Cross-cultural relationships

Culture is not only about the things we can see. It involves the beliefs, behaviours and values of a particular social group. Our cultural identity may include (but is not limited to) ethnicity, nationality, socioeconomic background, political affiliation, religion and race. We may be able to identify with aspects of several cultures.

Every culture affects our personal habits and preferences. There are many interesting dynamics and things to learn when people from different cultures come together, whether in a work context, social settings, or in more intimate relationships. When a couple come from different cultural backgrounds there are some additional challenges they may face, however. The loyalty we can often feel towards our own culture could challenge our attitudes. Couples in a cross-cultural relationship may experience some unexpected issues or misunderstandings as they learn about each other’s expectations. This could lead to potential problems related to each other’s cultural views.

Cross-cultural issues faced by couples can include differences in deeply embedded assumptions about norms in:

- Appropriate forms of communication within a partnership.

- Expected behaviour between the partners.

- Gender roles.

- Parenting tactics.

- Desirable behaviour in children.

- Household responsibilities such as chores.

- External responsibilities such as who and how the household will be represented in the community.

Other issues cross-cultural couples can face include:

- Loss of identity.

- Conflicts over differences in fundamental beliefs.

- Different methods of dealing with conflict.

- Struggles with unsupportive families.

- Language barriers (humour, communication, emotions).

Global relationships

Intercultural couples talk about dating.

Tips for overcoming issues in cross-cultural relationships:

- Learn as much as possible about your partner’s culture. Get first-hand experience of each other’s culture—visit their country, place of worship, learn their language.

- Be respectful of your partners religious beliefs.

- Find common ground in the beliefs and values – find a happy medium.

- Recognise that you may hold quite different patterns for what a healthy relationship looks like, or how it operates. This may require you to change your own views, and do some quite hard work to form a new shared pattern that works for your partnership.

- Educate and bring your children up to appreciate both cultures.

- Be patient.